Employee Monitoring Technology: What Are the Risks for California Employers?

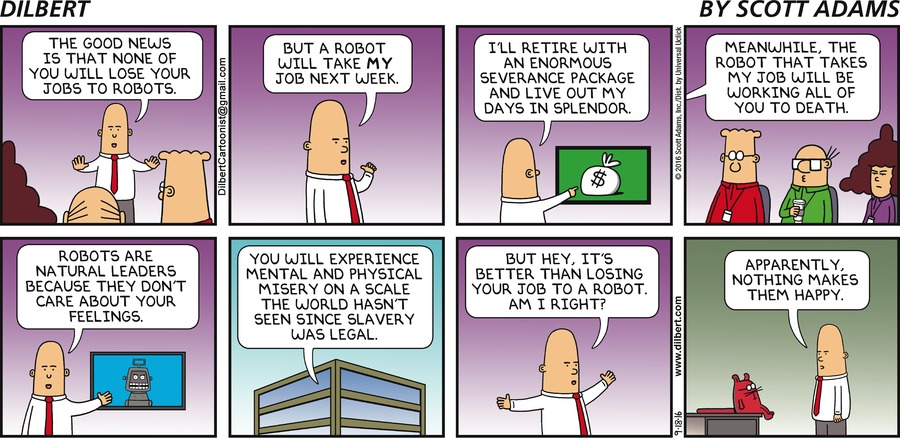

Hanging in my office is a Dilbert cartoon wherein a boss announces to his subordinates that, happily, they would not be replaced by robots. Unhappily, he would be replaced by a robot, bringing his unfortunate subordinates suffering “the world hasn’t seen since slavery was legal.”

In an apparent bid to outdo Dilbert’s employer, Amazon has patented an employee monitoring and assistance system that critics claim turns employees into cyborg “Amabots,” and could push already-exhausted workers over the edge of human endurance.

Amazon’s proposed biometric monitoring device, and theoretical efficiency enhancer, is a bracelet worn on the employee’s wrist. The bracelet uses radio frequency identification (“RFID”) technology to track every single movement the employee makes, and can vibrate to help guide the employee’s hand to the proper inventory bin. Amazon has not yet implemented the system and has not announced whether they plan to do so. But the proposed technology begs the question: Can a California employer even do that?

Common-Law Privacy Claims

The answer, for now, is unclear at best, but implementing such a system definitely carries legal risks. California employers who implement employee monitoring systems comparable to Amazon’s face potential liability for “intrusion” into an employee’s privacy, a common-law tort recognized in California. An employer will be liable for intruding into an employee’s privacy where they: (1) intentionally intrude into a matter, place, or conversation where the employee has a reasonable expectation of privacy, or (2) intrude in a manner “highly offensive” to a reasonable person.

In 2009’s Hernandez v. Hillsides, the California Supreme Court discussed an employee’s expectation of privacy at work in detail, describing a spectrum of the amount of privacy that is reasonable based on the circumstances of their workplace. At one end, California law is clear: areas where employees may be found in a state of undress, such as restrooms, locker and changing rooms, are off-limits for electronic surveillance. On the other end, the law is clear that there is very little reasonable expectation of privacy where “work is conducted in an open or accessible space within the sight and hearing of” coworkers, visitors, supervisors, customers and the general public, such as open cubicles or the sales floor of a department store. Somewhere in the middle are scenarios like the Hillsides case, where the employees had a reasonable expectation of some level of privacy based on the semi-private physical nature of their office, the lack of access by customers or the public, the ability to prevent themselves from being seen and heard, the ability to lock their door and prevent access, and their lack of notice that a camera was being installed.

The Supreme Court went on in Hillsides to note that forms of constant monitoring, such as video cameras, are particularly intrusive because the “unblinking lens” subjects employees to a higher level of scrutiny than human supervision would, and prevents the employee from preventing the dissemination of their image. It is not unreasonable to conclude that a California Court judging Amazon’s bracelet technology would find that it was also particularly invasive form of monitoring because of its similarly unblinking nature, and because it prevents the employee from preventing disclosure of even more intimate data about themselves: such as taking a moment to scratch themselves, adjusting their clothing or undergarments, performing grooming or hygiene activities, engaging in private conversations, using the restroom, or changing clothes. Employers might also run afoul of other laws by recording employees’ conversations and movements during meal and rest breaks: times and locations where employees have a reasonable expectation of privacy.

And intrusion is not the only privacy risk: California employers who store sensitive data, such as health or personal information, on RFID-enabled devices also risk liability under the common law tort of “public disclosure of private facts.” Because data stored on these devices can be accessed by hackers in close physical proximity to the RFID-enabled device, unauthorized disclosure of personal information is possible. Employers planning to maintain sensitive information on RFID-enabled devices that they require employees to carry with them should work closely with their technology department to ensure such data is protected from unauthorized access.

The Privacy Torts of Today Are Not the Privacy Torts of Tomorrow

As a legal concept, what constitutes a reasonable privacy interest is constantly evolving. That’s because determining whether an employee has a reasonable privacy interest includes, in part, a consideration of what is acceptable under current social norms. And the social norms seem to be moving in favor of ever-more-invasive forms of employee monitoring. While having employees microchipped seems unbelievable now, one Wisconsin company has already voluntarily microchipped almost half of their workforce, and they are currently developing an advanced chip that includes GPS, voice activation, and vital sign monitoring. In Sweden, voluntarily-microchipped people use their implants to unlock doors and purchase train tickets. Experts estimate that the in the next generation or two, microchipped humans will become the norm. As social norms expand, and more people begin using similar technology in everyday life, ever-more invasive types of employee monitoring may become permissible, even in California.

Other Legal Risks of Biometric Monitoring

Other areas of risk include claims of discrimination and wiretapping. Discrimination claims can arise when employers base employment decisions on data gathered from employee monitoring technology. Simply terminating the slowest performers could create patterns of terminations that display disability- or gender-related discrimination, and create corresponding liability for employers.

Wiretapping claims are most likely where the employer utilizes technology with voice activation and/or the capacity to record voices. California’s wiretapping statute requires both parties’ consent to record private calls or conversations. While employers can obtain consent from their own employees, they will not be able to obtain the consent of every person the employee interacts with, opening the employer up to wiretapping claims from individuals who were recorded without their knowledge or consent.

Tips for Today’s Employers

Employers seeking to improve efficiency through biometric monitoring of employees must balance their interest in efficiency and cost-savings against employee morale concerns and the ethical implications of ever-increasing performance demands. As demonstrated by the stories emerging from Amazon’s own warehouses, at some point efficiency can give way to cruelty, causing exhausted employees to suffer physically and mentally or risk being terminated. Employers should also consider the negative impact on goodwill and public reputation the implementation of such a system may create.

All California employers should work closely with employment counsel of their choosing to discuss all the risks and benefits of implementing any system of employee monitoring. Counsel can also assist employers with drafting policies, procedures, and notices to decrease the risk of privacy or discrimination claims. Employers subject to a collective bargaining agreement face additional hurdles and should be sure to work closely with their legal counsel.

Stefanie Renaud is an associate in Hirschfeld Kraemer LLP’s Santa Monica office. For more information, please contact her at srenaud@hkemploymentlaw.com.

Dilbert cartoon © Andrews McMeel Publishing. Reprinted with permission.